I posed the following short prompt to ChatGPT 40 Research: “Gather information about David Murdock and how he treated Kannapolis.” The AI asked me to be more specific: “For example, are you looking for historical background, business investments, economic impact, community relationships, controversies, or something else?” I responded with use all examples. Below is what was generated, including sources.

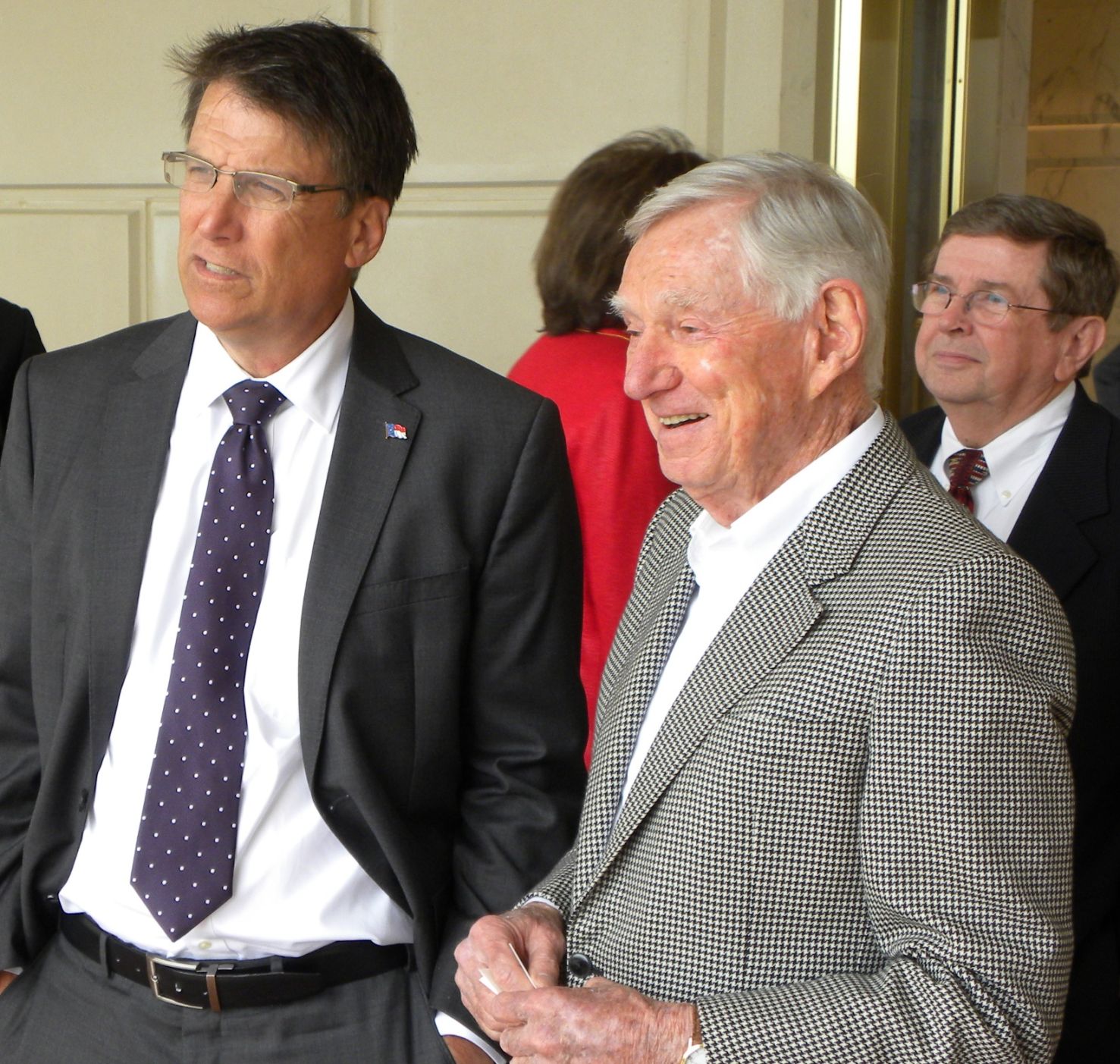

David Murdock, right, looks across the N.C. Research Campus in 2015 with N.C. Governor Pat McCrory. Kannapolis Mayor Darrell Hinnant is in the background. I shot this photo for the Independent Tribune.

David Murdock and Kannapolis: From Cannon Mills to a Research Campus

David Murdock – Background and Business Ventures

David Howard Murdock (born 1923) is an American billionaire entrepreneur known for a rags-to-riches story and diverse business empire. A ninth-grade dropout from Missouri, Murdock built his fortune through real estate development and savvy investments in the post-war decades siteselection.com. By the 1980s he was counted among America’s wealthiest individuals, eventually taking over Castle & Cooke, a nearly bankrupt Hawaiian company, in 1985 and with it becoming owner and chairman of Dole Food Company, one of the world’s largest fruit and vegetable producers en.wikipedia.orgsiteselection.com. Over his career, Murdock’s ventures have spanned mining, petroleum, food production, and real estate. He is also known for his personal passion for health and nutrition – a focus that would later shape his investments in North Carolina – and has openly stated ambitions of longevity, crediting diet and research as keys to extending human life archive.orgarchive.org.

Throughout his life, Murdock has engaged in major philanthropic and development projects. Notably, he funded the David H. Murdock Research Institute and other initiatives aimed at scientific discovery in nutrition and disease prevention. However, he has also drawn controversy for his aggressive business tactics. His path eventually intertwined deeply with Kannapolis, North Carolina, a textile mill town that became the stage for some of his most ambitious – and debated – projects.

Cannon Mills Acquisition and Early Involvement in Kannapolis (1982–1986)

Murdock’s first major foray into Kannapolis came in 1982, when his holding company Pacific Holding purchased the town’s economic lifeblood: Cannon Mills kannapolisnc.gov. Cannon Mills was a giant textile manufacturer (once the world’s largest producer of towels and sheets) and the backbone of Kannapolis, which at the time was an unincorporated mill village largely built and operated by the Cannon family. Murdock acquired Cannon Mills for roughly $413 million in 1982 ncnewsline.com, making a splash as an outside investor in the traditionally close-knit mill community. He invested in modernizing the facility and launched a $20 million downtown renovation, including development of the Cannon Village shopping district, to revitalize the area kannapolisnc.gov. In 1984, as the town grew, Kannapolis residents voted to incorporate as a city – a period when Cannon Mills under Murdock still employed tens of thousands of people locally kannapolisnc.gov.

Despite these investments, Murdock’s tenure as mill owner was brief and contentious. He quickly instituted cost-cutting measures: after financing the takeover with significant debt, Murdock used Cannon Mills’ own profits to pay off acquisition loans, eliminated about 2,000 jobs, and sold off hundreds of company-owned mill houses en.wikipedia.org. Most controversially, he terminated the company’s pension plan, which had been fully funded at about $100 million, and redirected the funds. Approximately $36 million was reportedly taken for Murdock’s personal investments, while the remainder was used to buy annuities from Executive Life Insurance for the employees’ pensions en.wikipedia.org. When Executive Life later collapsed due to poor investments, Cannon Mills retirees saw their pension payments dramatically reduced en.wikipedia.org. This move – effectively “raiding” the workers’ pension pool – generated anger and lasting resentment in the community. “It was my money… He ripped the people off,” one 48-year mill veteran said, reflecting widespread bitterness among Kannapolis pensionersf acingsouth.org. The episode became a textbook example of aggressive 1980s corporate takeovers and their human toll, leaving “hard feelings in the community that still exist,” as a local official later remarked ncnewsline.com.

In 1985, after just three years, Murdock exited the textile business in Kannapolis by selling Cannon Mills to Fieldcrest Mills (forming Fieldcrest-Cannon) kannapolisnc.gov. The sale and subsequent consolidation led to further layoffs, particularly among white-collar staff kannapolisnc.gov. Murdock had profited from the deal, but many locals felt burned by his short tenure. He did make some charitable gestures – for example, donating land and funds to build the David H. Murdock Senior Center in Kannapolis in the late 1980s facingsouth.org – yet the overall impression for some was of a “corporate raider” who came to town, disrupted lives, and left. Indeed, by the time he departed, Murdock had acquired and then shed a vast portion of Kannapolis’s built environment, including not just the mill but much of the downtown property. This period cemented a mixed legacy: he had brought new retail investment (Cannon Village) and modernized facilities, but also contributed to job losses and a pension debacle that locals would not forget ncnewsline.com facingsouth.org.

Return to a Shuttered Mill Town – Laying the Groundwork for a Research Campus

After Murdock’s exit, Kannapolis’s textile fortunes continued to waver under different owners. Fieldcrest-Cannon eventually was bought by Pillowtex Corporation in 1997 kannapolisnc.gov. By the early 2000s, globalization and declining competitiveness took their toll on American textiles. Pillowtex went bankrupt, and in July 2003 the Kannapolis mill closed, triggering 4,340 layoffs in a single day – the largest one-day job loss in North Carolina’s history kannapolisnc.gov. The shutdown was economically and socially devastating: an entire way of life centered around the mill abruptly ended. Local and state officials compared the impact to a natural disaster, as thousands of mostly blue-collar workers (many with limited education or skills outside the mill) suddenly found themselves unemployed psmag.compsmag.com. Kannapolis, a city of about 40,000 built on textiles, was in danger of becoming a ghost town defined by a sprawling, empty factory at its heart.

It was at this low point that David Murdock re-entered the picture. In late 2004, the 81-year-old billionaire – who still kept a home in the area and owned pieces of downtown real estate (the former Cannon Village) – returned to Kannapolis and purchased the idle Pillowtex plant (the old Cannon Mills Plant One) at auction for $6.4 million salisburypost.com. Standing in front of the shuttered mill in 2005, Murdock unveiled an ambitious vision to transform Kannapolis from a fading textile town into a futuristic center of science. He announced plans for a $1 billion-plus research campus devoted to nutrition, health, and biotechnology, to be built on the ruins of the mill ncnewsline.com kannapolisnc.gov. In what he called a “scientific and economic revitalization project,” Murdock promised to essentially rebuild downtown Kannapolis as a hub for cutting-edge research – a project he believed could ultimately generate tens of thousands of jobs and breathe new life into the communityncnewsline.com siteselection.com.

Local leaders and state officials eagerly backed the proposal. Politicians rallied around Murdock’s idea, seeing it as a much-needed lifeline for the region ncnewsline.com. The plan was grand in scale: Murdock – then the owner of Dole Food and CEO of Castle & Cooke – envisioned a 350-acre “biopolis” campus featuring state-of-the-art laboratories, academic institutes, commercial space and residential development. Early projections touted 100 biotech companies, 5,000 scientists, and as many as 30,000–35,000 new jobs on or around the campus once fully realized ncnewsline.com siteselection.com. He spoke of bringing “the most prestigious universities” and top scientific minds to Kannapolis, and turning the whole town into a giant “think tank” for nutrition and disease researchwfae.orgsiteselection.com.

Murdock’s personal motivation blended business with philanthropy. He had become an ardent health and nutrition enthusiast, especially after losing his wife to cancer years earlier, and often expressed a desire to find cures for major diseases wfae.org. “I was very devastated when I lost my wife and I thought I would… do something about trying to solve some of the problems,” he said, explaining his drive to create a research center focused on health and longevity wfae.org. With North Carolina’s universities on board and public agencies offering support, Murdock’s bold plan began taking shape.

The North Carolina Research Campus – Murdock’s Major Investment in Kannapolis

The David H. Murdock Core Laboratory at the North Carolina Research Campus in Kannapolis opened in 2008. Built on the former mill site, this flagship building houses advanced research equipment and symbolizes the city’s transformation from textiles to biotechnology.

In 2006, demolition crews tore down the massive 5.8-million-square-foot textile mill complex – an area almost as large as the Pentagon – to clear the way for Murdock’s new campus siteselection.com. Construction on the North Carolina Research Campus (NCRC) officially broke ground that year, and by 2008 the first buildings were completed. The centerpiece was the David H. Murdock Research Core Laboratory, a 311,000-square-foot facility crowned with a dome, outfitted in marble and high-tech instrumentation archive.org. This and other buildings rising from the site completely changed Kannapolis’s skyline: the old smokestacks emblazoned with “Cannon” and “Fieldcrest” are gone, replaced by red-brick edifices akin to an academic village wfae.org.

Murdock poured a significant amount of his own fortune into the project. By 2008 he had invested an estimated $400 million of personal funds in the campus’s development wfae.org, a figure that would grow over time (surpassing $600 million by 2013) as he bankrolled operations and construction when other funding lagged salisburypost.com. The State of North Carolina also committed support, allocating about $30 million annually to help participating public universities and a local community college operate on-site programs and workforce training initiatives wfae.org. In addition, the city and county provided infrastructure assistance and tax incentives to facilitate the massive redevelopment.

From the outset, the NCRC was a public-private partnership of unusual scale. Murdock’s development firm Castle & Cooke built and managed the campus, while eight universities (including Duke University, UNC Chapel Hill, NC State, UNC Charlotte, NC A&T, NC Central, Appalachian State, and UNC Greensboro) signed on to establish research centers in fields like nutrition, genomics, agriculture, and biotech kannapolisnc.gov. The campus also attracted government and industry tenants: for example, the Cabarrus Health Alliance (the county public health agency) located offices and labs there, and early corporate partners included PepsiCo and PPD (Pharmaceutical Product Development) which took space in the Core Lab building wfae.org. Murdock even lured his own company, Dole, to participate – Dole’s Nutrition Institute and laboratories became part of the campus roster salisburypost.com salisburypost.com. Other major companies that joined included General Mills and Monsanto, both interested in research on foods and crop science archive.org salisburypost.com. At its peak optimism, plans called for 100–200 start-ups and private labs to eventually find a home in Kannapolis’s “biopolis”siteselection.com.

The North Carolina Research Campus formally opened with great fanfare. At an October 2008 ribbon-cutting, dignitaries proclaimed a new era for Kannapolis. UNC system president Erskine Bowles heralded the “dramatic effect” the facilities would have on the region’s economy and even “the entire world” through scientific discovery wfae.orgwfae.org. The vision was not only to create jobs but also to position Kannapolis as a world-class center for nutrition and disease-prevention research. In practice, the campus features collaborative efforts that leverage its unique co-location of multiple institutions. For example, it established the MURDOCK Study (an acronym using Murdock’s name) – a long-term medical research project enrolling over 12,000 local residents to donate blood and genetic samples for studying health trends and diseases archive.org. The campus built one of the world’s largest bio-repositories to store these samples, aiming to advance personalized medicine. This initiative has been a hallmark scientific project tying the community to the campus’s research mission.

Murdock’s redevelopment plan also extended beyond labs. As originally conceived, the project would include a new Kannapolis City Hall, retail shopping areas, and hundreds of new housing units to create a live-work community around the scientists siteselection.com. Indeed, the NCRC is nestled in downtown Kannapolis, and its presence spurred the city to pursue broader downtown revitalization. Over time, additional facilities have been built: a medical office plaza, a data center, and the Rowan-Cabarrus Community College Biotechnology Training Center on campus, among others salisburypost.com kannapolisnc.gov. The community college’s programs at NCRC train local students for biotech and laboratory jobs, reflecting Murdock’s intent that education and workforce development go hand-in-hand with research activity kannapolisnc.gov. What was once an expanse of vacant industrial land became, within a decade, one of the largest urban redevelopment projects in U.S. history by area kannapolisnc.gov – a physical testament to Murdock’s determination to reinvent Kannapolis.

Economic and Social Impacts on the Kannapolis Community

Job Creation and the Local Economy: Murdock’s involvement in Kannapolis has had a profound but complex economic impact. In the short term, the collapse of Cannon Mills/Pillowtex in 2003 wiped out over 4,300 jobs and devastated the local economy kannapolisnc.gov. The Research Campus was envisioned as a way to replace and exceed those lost jobs, shifting the employment base from manufacturing to knowledge-based industries. However, the reality fell far short of initial projections. By 2013 – five years into the campus’s operation – only about 600 people worked on the NCRC, versus the thousands promised salisburypost.com salisburypost.com. A 2016 report noted roughly 1,000 jobs on campus, “nothing close to the 20,000 jobs on and off campus” that Murdock’s team had once predicted archive.org. Moreover, many of the scientific and technical jobs created required advanced degrees and drew talent from outside Kannapolis. Developers estimated roughly half of NCRC employees lived in the local (Cabarrus/Rowan County) area and the rest commuted from elsewhere salisburypost.com salisburypost.com. This meant the immediate benefit to former mill workers – many of whom had only high school education or less – was limited. One local business owner observed nearly a decade in, “I don’t see where it’s helped a lot” in terms of everyday folks finding work archive.org.

That said, the campus did inject much-needed economic activity and prevent complete collapse of downtown. It created new types of jobs (scientists, lab technicians, support staff) that had never existed in Kannapolis before. The influx of state funding for university research and training programs also brought stable public-sector employment to the city. Local services and real estate have gradually started to recover: new restaurants, shops, and apartments have opened to cater to the growing professional workforce. City officials credit the NCRC as the anchor that enabled Kannapolis to attract additional investment (for example, a biomedical data center and a minor league baseball stadium in subsequent years). By the mid-2020s, Kannapolis reported a more diversified economy, with life-sciences, healthcare, and education forming a second pillar alongside the remaining manufacturing in the region. The downtown area, once eerily empty after the mill closure, has shown signs of rebirth – so much so that an official city statement in 2025 declared the research campus “pivotal to the City’s revitalization” wbtv.com.

Real Estate and Urban Development: Murdock’s ventures dramatically altered the physical landscape of Kannapolis. The demolition of the huge mill opened up 350 acres in the city center for redevelopment. In place of looming brick factory buildings and worker housing, the campus introduced modern infrastructure – landscaped grounds, gleaming lab buildings, and streets designed for a mix of pedestrians and traffic rather than factory shift changes. Property values in the immediate area have risen from their post-layoff nadir, although large portions of developable land remained under Castle & Cooke’s ownership for years, awaiting further construction as the project evolved. Kannapolis city government eventually decided to take a more direct hand in shaping downtown’s future: in 2015, the City of Kannapolis negotiated the purchase of the remainder of the Murdock-owned historic downtown (the Cannon Village retail district) in order to renovate storefronts, add a new farmers market, and encourage private developers to build apartments and shops kannapolisnc.gov kannapolisnc.gov. This public initiative, made possible only because the Research Campus had put Kannapolis “on the map” again, is now resulting in a more vibrant, mixed-use downtown. In short, Murdock’s investment served as the catalyst for one of the nation’s most ambitious mill-town transformations, even if the transformation took longer than hoped. An academic review of Kannapolis’s journey described it as an experiment in revitalizing a small city: a risky bet that a one-company textile town could reinvent itself as a diversified, innovation-driven economy beeckcenter.georgetown.edu psmag.com.

Education and Scientific Initiatives: A significant positive impact of Murdock’s involvement has been expanded educational and research opportunities in Kannapolis. The presence of eight major universities on the NCRC has effectively turned the city into an extension campus for those institutions, bringing professors, students, and research grants into the community. Local students have opportunities to engage with world-class researchers or enroll in programs (like UNC Chapel Hill’s Nutrition Research Institute in Kannapolis, which opened a 126,000 sq. ft. facility in 2008 lib.ncsu.edu). The Rowan-Cabarrus Community College established its Biotechnology and healthcare programs at the campus, allowing residents to gain new technical skills and certificates for biotech manufacturing, lab work, and clinical research support kannapolisnc.gov. As RCCC’s president noted, having these resources “has been immensely helpful” to the college and by extension to local workforce development wbtv.com.

On the scientific front, the collaborative model at Kannapolis has led to research outputs in nutrition science and health. Studies on the links between diet and diseases have been launched, and companies like Dole and General Mills have conducted food research there. While it is too early to claim any major scientific breakthrough directly from NCRC, the campus’s advocates highlight the unique integration of multiple universities in one location as a legacy that is advancing knowledge in food science and preventive medicine wbtv.com. Murdock’s early “foresight to open a research campus focusing on nutrition well before it was a popular topic made a massive impact on the field,” one university official stated, underscoring that Kannapolis is now firmly on the map in scientific circles for its contributions to understanding how food and exercise affect health wbtv.com. In summary, although the economic payoffs materialized slower and smaller than hoped, the social and intellectual capital generated by Murdock’s project has started to reshape Kannapolis’s identity – from a company town to a “city of learning” with new pride in its role tackling global health challenges.

Community Reception: Praise, Hopes and Skepticism

Public reaction in Kannapolis to David Murdock’s actions has evolved over the decades, swinging between gratitude and wariness. Initial impressions in the 1980s were largely negative among mill workers and retirees. Murdock’s abrupt changes at Cannon Mills – especially the pension termination – fostered distrust. He was seen by many as an outsider who didn’t understand or prioritize the community’s well-being. Local politicians and clergy in the 1980s decried the harm done to the workers; even years later, officials recalled the “unrest” and bitter feelings left in Murdock’s wake ncnewsline.com. This sentiment lingered such that when he returned in 2004, long-time residents remembered and “had heard his promises before,” as one reporter noted ncnewsline.com. Some older residents cautioned that while the new promises of revival sounded good, they were taking a “wait and see” approach due to past experience.

Nonetheless, the dire situation after the Pillowtex closure made many in Kannapolis willing to embrace Murdock’s comeback. In 2005, community members were described as both grateful and cautiously hopeful that he might rescue the town ncnewsline.com ncnewsline.com. “Residents hope he succeeds,” the Raleigh News & Observer reported, noting that local people, faced with a “forlorn town” and evaporated jobs, were pinning their hopes on the billionaire’s grand plan ncnewsline.com. The prospect of 30,000+ new jobs and a bustling high-tech campus was almost unimaginably positive for families who had been struggling since the mill’s closure. Many showed support – attending town hall meetings, applauding announcements – simply because any credible plan was better than watching weeds overgrow the abandoned mill. Political leaders at the city, county, and state levels were especially supportive, crediting Murdock for investing in a community that many others had written off. Governor Mike Easley and later governors publicly praised the NCRC initiative, and the state legislature committed funds, reflecting a generally positive official reception.

As the Research Campus took shape, public opinion remained mixed. There was genuine appreciation for the new facilities and intrigue about the high-profile research being conducted in Kannapolis. Some residents took pride in their city being associated with curing diseases or improving nutrition. Young people and those able to get new jobs on campus were enthusiastic about the opportunities. One longtime resident, watching the new buildings open, said it was sad to see the old mill go but “you’ve got to move on… hopefully this is a good thing for Kannapolis”, capturing the bittersweet but optimistic view many heldwfae.org. There was also admiration for Murdock’s personal commitment – the fact that a 80-something tycoon was regularly flying in, touting small-town Kannapolis as the future “health capital,” impressed some folks. As one local artist put it in retrospect, “I do believe he saved the town” from dereliction by stepping in when he did psmag.com psmag.com.

On the other hand, skepticism and criticism persisted, especially as years passed and the grand promises did not fully materialize. By the 2010s, some townspeople and observers openly questioned whether Kannapolis was actually better off. They noted the lack of substantial job creation for locals and the slow pace of private investment beyond the campus itself. Empty storefronts and struggling small businesses in parts of downtown fueled a sense that the renaissance hadn’t reached everyone. “Kannapolis… often think the mogul didn’t see through his biggest plans for the area,” one Charlotte TV news report noted about local attitudes, referring to Murdock’s inability to deliver the scale of development initially hyped wbtv.com wbtv.com. Indeed, the sight of highly educated researchers driving in from Charlotte or Raleigh for work – while many former mill workers ended up in lower-paying retail or service jobs – led to some resentment. The perception of exclusivity – an elite “campus on a hill” somewhat disconnected from everyday Kannapolis – was a challenge the NCRC had to actively work to overcome. Community outreach programs (like public science events and health fairs) were initiated in response, and over time integration has improved. Still, interviews in the mid-2010s found local merchants saying business from the campus was underwhelming and residents asking when the “100 companies” would actually show up archive.org salisburypost.com.

By the time of Murdock’s passing in 2025 at age 102, sentiments had begun to coalesce into a clearer legacy view. The positive camp points out that Kannapolis did not become a ghost town and now has a future oriented around education and health. City officials and many residents publicly expressed gratitude for “his investment in the North Carolina Research Campus” and the fact that it gave Kannapolis a second life wbtv.com. Tributes emphasized that Murdock “turned it around to be something that was at the heart of the city and a thriving downtown” – a transformation from the tragedy of the mill closure, as Dr. Cory Brouwer of UNC Charlotte put itwbtv.com wbtv.com. The critical camp, however, remembers the unfulfilled job numbers and the early pension ordeal. They acknowledge the campus’s benefits but temper it with, “he didn’t fully deliver on what he said,” a view that “divided opinion across the region” about Murdock wbtv.com. In sum, community reception to Murdock’s Kannapolis chapter has ranged from treating him as a visionary benefactor to eyeing him as an unreliable salesman – and many individuals likely hold a bit of both views.

Controversies and Criticisms of Murdock’s Kannapolis Dealings

David Murdock’s business dealings in Kannapolis have not been without controversy. The most notorious episode remains the 1980s Cannon Mills pension fund controversy. Murdock’s decision to terminate the pension plan and use its assets for corporate purposes was widely condemned. Thousands of retired mill workers, who had labored a lifetime for modest pensions, suddenly saw their retirement security jeopardized due to decisions made in distant boardrooms facingsouth.org. Although legal at the time under lax regulations, this move was viewed as unethical by the community and labor advocates. It became a high-profile example in debates about corporate raiders in the ’80s; even a U.S. Senate hearing highlighted the plight of Kannapolis retirees whose pensions were cut by 30% after the Executive Life annuities failed facingsouth.org. Murdock eventually wrote personal checks totaling $800,000 to some retirees as partial restitution facingsouth.org and funded a senior center, but these gestures did little to erase the bitterness. To this day, the pension incident is cited in North Carolina as a case of a businessman prioritizing profit over people, and it tarnished Murdock’s reputation locally for years.

Another criticism revolves around overpromising and underdelivering with the North Carolina Research Campus. Murdock’s initial promises – 100 companies, 30,000 jobs, a booming biotech economy – proved far too optimistic ncnewsline.com ncnewsline.com. As the campus developed more slowly, skeptics accused him of selling false hope to a desperate town. The contrast between the rhetoric and the reality became a point of contention. By 2016, the campus had only a fraction of the projected jobs, and Kannapolis still struggled with economic recovery. “The campus now employs more than 1,000 people, nothing close to the 20,000 jobs… predicted,” noted a PBS NewsHour report, highlighting the shortfall archive.org. Moreover, many of those jobs did not directly go to former mill workers, which drew criticism that the revitalization had a limited trickle-down effect. The fact that Murdock’s own real estate company stood to benefit from any appreciation in the land value and facilities (given Castle & Cooke’s ownership of the campus) also led some to question his altruism. Detractors wondered if the project was in part a vanity project or a way to increase the value of his holdings with public subsidies, especially when progress stalled during the Great Recession and required him to reinvest more capital salisburypost.com.

There were also concerns about transparency and governance. The NCRC was largely driven by Murdock’s private company, which at times led to tension about control. Local governments essentially entrusted the redevelopment of downtown to one man’s vision. While there were no major scandals in the construction, some critics felt that public input was limited – the average Kannapolis resident had little say in the campus’s development direction, despite taxpayer money supporting parts of it. This “top-down” approach fueled wariness, though city officials were generally on board due to the lack of alternatives.

Additionally, the ethical dimension of research at Kannapolis drew some critical attention. The MURDOCK Study’s collection of thousands of residents’ DNA and health data, for example, raised questions about consent and benefit: a Pacific Standard article in 2014 asked pointedly how much the average participant would share in the gains if any discoveries led to profitable innovations psmag.com psmag.com. The campus administrators responded by implementing standard protections (informed consent, data encryption) and emphasizing the altruistic aims of the research archive.orgarchive.org. While no major ethical breaches have come to light, the scenario of an economically distressed town “handing over its DNA” to a billionaire’s project was a provocative storyline that some journalists critiqued psmag.com psmag.com.

In the local political arena, Murdock’s dominance in Kannapolis’s downtown real estate was occasionally contentious. Owning so much property (“at one point he owned most of the City of Kannapolis,” WBTV noted) meant the city’s fate was tied to his decisions wbtv.com wbtv.com. For instance, when he delayed or scaled back building plans during the 2008–2010 recession, Kannapolis had to be patient or seek new strategies. Eventually, in 2015, Murdock agreed to sell a large portion of the downtown district to the city at a reported $5.5 million, a move welcomed by officials to diversify development and remove “all the eggs” from Murdock’s basket (this allowed for new developers to come in and for the city to guide redevelopment more directly) kannapolisnc.gov. While this turned out to be a cooperative outcome, it underscores that for years one private entity’s priorities heavily influenced the public landscape – a situation not without critics concerned about accountability.

In summary, David Murdock’s involvement in Kannapolis has been controversial but transformational. He attracted criticism for the human cost of his business maneuvers (layoffs and pension cuts in the 1980s) and for the gaps between promises and results in his 2000s revitalization effort. At the same time, he is credited with bold action that prevented Kannapolis from economic free-fall and with introducing a new industry that may secure the city’s future. The dual nature of his legacy is perhaps best captured by the fact that he “divided opinion” in the region wbtv.com. As Kannapolis officials now hail the Research Campus and its ongoing contributions, they also acknowledge that the growth was “far below the original projections for over a decade”wbtv.com. Murdock himself remained steadfast in his vision – even into his 90s, visiting regularly and pushing for new partners salisburypost.com – a determination that won him respect even from former skeptics.

Ultimately, Kannapolis today stands as a city reinvented, in large measure due to David Murdock’s gambles. The textile era that defined it for a century has given way to an era of biotech and health research. This rebirth did not come easy and is not complete, but the foundation laid by Murdock’s investments altered the city’s trajectory. His story in Kannapolis is a study in contrasts: corporate ruthlessness vs. visionary philanthropy, grand ambition vs. practical outcome, skepticism vs. gratitude. Both the praise and the criticisms are well-earned. And as Kannapolis moves forward, the full impact of David Murdock’s involvement – economic, social, and scientific – will continue to be assessed by those who live and work in the community he helped rebuild.

Sources:

- City of Kannapolis – Official History and Project Descriptionskannapolisnc.gov kannapolisnc.gov kannapolisnc.gov kannapolisnc.gov

- Charlotte Observer/Raleigh News & Observer (via NC Newsline) – Jonathan B. Cox, “Kannapolis grateful, wary about promises from Murdock” (Sept. 2005)ncnewsline.comncnewsline.com

- WFAE (NPR Charlotte) – Simone Orendain, “Ribbon Cutting at the NCRC” (Oct. 21, 2008)wfae.org wfae.org

- Salisbury Post – Emily Ford, “NC Research Campus behind schedule but picking up steam” (July 30, 2013)salisburypost.com salisburypost.com salisburypost.com

- PBS NewsHour – “How a research campus deals with ethical questions in one NC town” (May 2016) archive.org archive.org

- Pacific Standard – Lisa Rab, “Sequenced in the U.S.A.: A Desperate Town Hands Over Its DNA” (2014)psmag.compsmag.com

- WBTV (Charlotte) – David Hodges, “NC businessman David Murdock dies at 102” (June 10, 2025)wbtv.com wbtv.com

- Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies – Chris Kromm, “Through the Mill” (Oct. 1991)facingsouth.org facingsouth.org

- Site Selection Magazine – “Murdock’s Biopolis” (Nov. 2005) siteselection.com siteselection.com

- NCpedia – “Cannon Mills” (Kelly Agan, 2006) en.wikipedia.org and related historical archives.